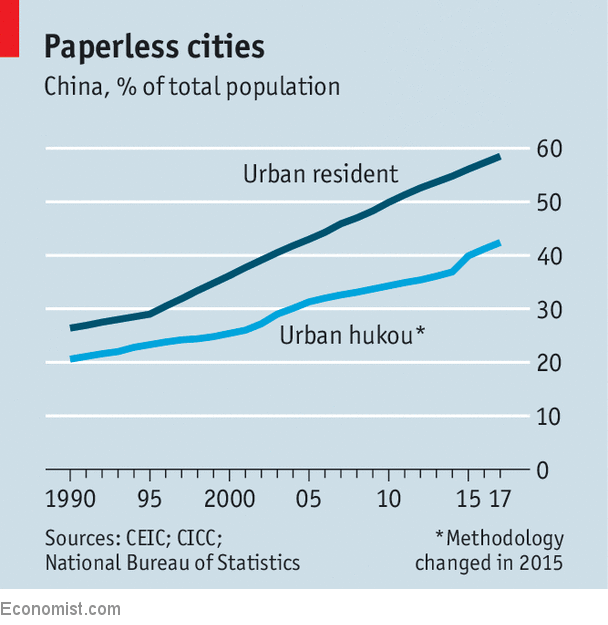

CHINA’S urbanisation is a marvel. The population of its cities has quintupled over the past 40 years, reaching 813m. By 2030 roughly one in five of the world’s city-dwellers will be Chinese. But this mushrooming is not without its flaws. Rules restricting migrants’ access to public services mean that some 250m people living in cities are second-class citizens (see chart), who could in theory be sent back to their home districts. That, in turn, has crimped the growth of China’s cities, which would otherwise be even bigger.

CHINA’S urbanisation is a marvel. The population of its cities has quintupled over the past 40 years, reaching 813m. By 2030 roughly one in five of the world’s city-dwellers will be Chinese. But this mushrooming is not without its flaws. Rules restricting migrants’ access to public services mean that some 250m people living in cities are second-class citizens (see chart), who could in theory be sent back to their home districts. That, in turn, has crimped the growth of China’s cities, which would otherwise be even bigger.

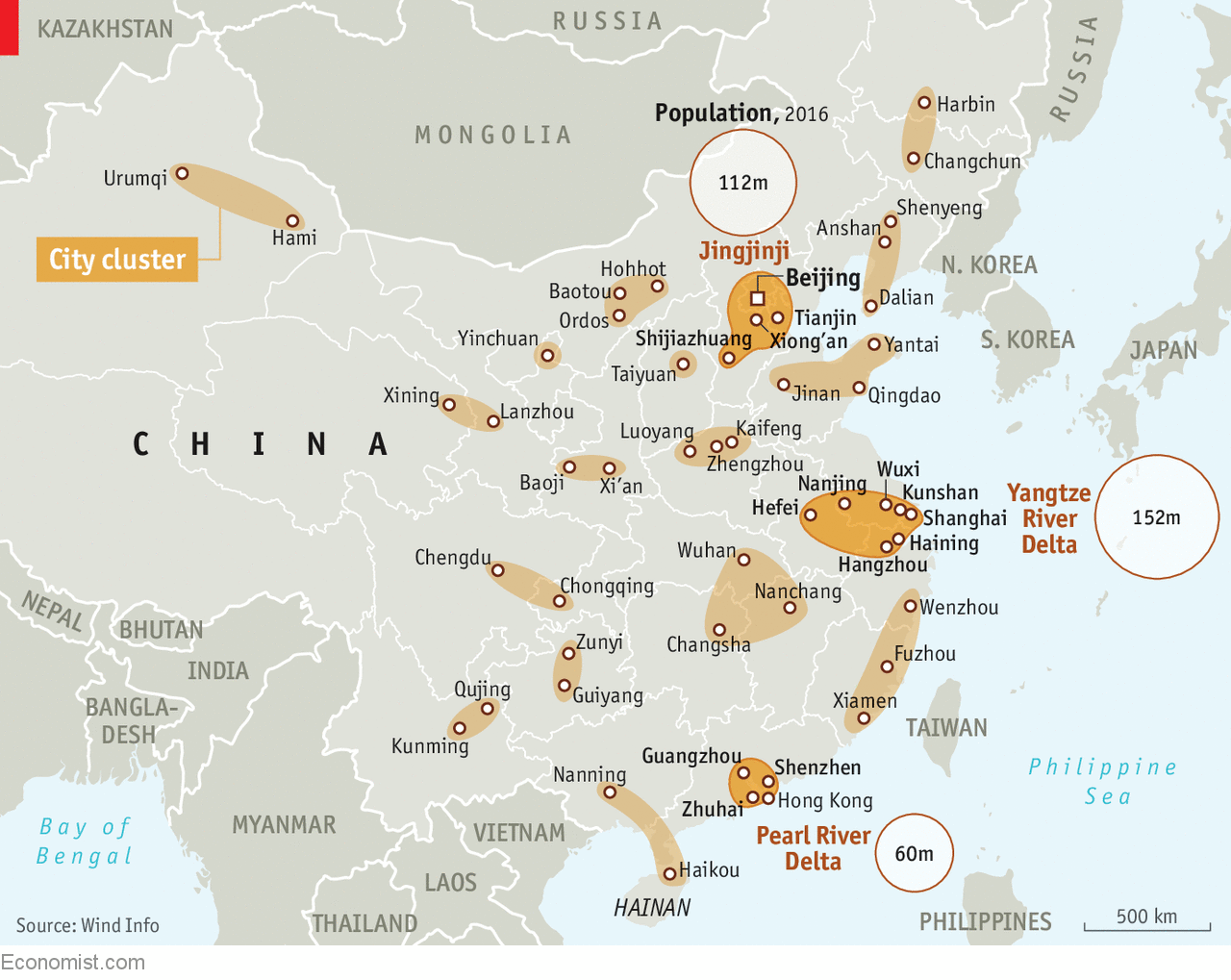

Restraining pell-mell urbanisation may sound like a good thing, but it worries the government’s economists, since bigger cities are associated with higher productivity and faster economic growth. Hence a new plan to remake the country’s map. The idea is to foster the rise of mammoth urban clusters, anchored around giant hubs and containing dozens of smaller, but by no means small, nearby cities. The plan calls for 19 clusters in all, which would account for nine-tenths of economic activity (see map). China would, in effect, condense into a country of super-regions. Three are already well on track: the Pearl River Delta, next to Hong Kong; the Yangtze River Delta, which surrounds Shanghai; and Jingjinji, centred on Beijing.

For some urban planners, the strategy is beguiling. They see the clusters as engines for growth that could transform China into a wealthy, innovative powerhouse. But others think it is a trap—a government-driven exercise in development that will lead to gridlock and waste.

Hu Qiuping, a safety manager for a chemicals company, is in the urban vanguard. She lives in Wuxi, a city of 6m about 150km west of Shanghai. A trip between the two used to take a couple of hours. Today the bullet train takes just 29 minutes. Every Monday and Friday she works in Wuxi, inspecting the chemicals factory. From Tuesday to Thursday she travels to the firm’s headquarters in Shanghai. She could have based herself in either city, but living costs were much lower in Wuxi. At first she wondered whether her commute was unusual. It was not. “I see familiar faces on the train every day,” she says.

For those in bedroom communities near London or Manhattan, Ms Hu’s train rides probably sound familiar. But three features make China’s super-regions exceptional. The first is scale. The biggest existing city cluster in the world is greater Tokyo, home to some 40m people. When it is fully connected the Yangtze delta, where Ms Hu is based, will be almost four times as big, with 150m people. The average population of the five biggest clusters that China hopes to develop is 110m. Part of the reason is that the physical area of most of the Chinese clusters will also be bigger. The most prosperous, the Pearl delta, is expected to cover 42,000 square kilometres, about the same as the Netherlands.

For those in bedroom communities near London or Manhattan, Ms Hu’s train rides probably sound familiar. But three features make China’s super-regions exceptional. The first is scale. The biggest existing city cluster in the world is greater Tokyo, home to some 40m people. When it is fully connected the Yangtze delta, where Ms Hu is based, will be almost four times as big, with 150m people. The average population of the five biggest clusters that China hopes to develop is 110m. Part of the reason is that the physical area of most of the Chinese clusters will also be bigger. The most prosperous, the Pearl delta, is expected to cover 42,000 square kilometres, about the same as the Netherlands.Given that spread, it might seem nonsensical to talk of the clusters as unified entities. But the second point is the speed of transport links, notably the bullet trains between cities. This expands the viable area of China’s clusters. The Jingjinji region around Beijing has five high-speed train lines today. By 2020 there should be 12 more intercity lines, and another nine by 2030. Towns that are woven into the networks can see their fortunes change almost overnight. Plans for a new intercity train to Haining, a smaller city in the Yangtze River Delta, partly explain a doubling of house prices there. “The way that we measure distances has changed from space to time,” says Ren Yongsheng of Vantown, a property developer in Haining.

The third difference is the top-down nature of the clusters. China is far from alone in wanting to knot cities together. “Cluster policy” has been in vogue in urban planning for years, with governments trying to devise the right mix of infrastructure and incentives to conjure up the next Silicon Valley, or something like it. But China has intervened more heavily than most. To encourage people to disperse throughout clusters, it has raised the barriers to obtaining a hukou, or official residency permit, in the wealthiest cities and lowered them in smaller ones nearby. Whereas Shanghai is picky about granting permits to migrants, Nanjing, to its west, has flung its doors open to university graduates. As construction gets under way in Xiong’an, a new city designed to relieve pressure on Beijing, efforts to push people out of the capital could become more aggressive. The scenes of police forcing thousands of migrant workers to leave Beijing last winter might prove to have been a preview.

The concept of city clusters is grounded in the theory of agglomeration benefits, which holds that the bigger the city, the more productive it is. A large, integrated labour market makes it easier for employers to find the right people for the right jobs. As companies gather together, specialised supply chains can take shape. Knowledge also spreads more easily. In advanced countries, the doubling of a city’s population can increase productivity by 2-5%, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a club mostly of rich countries. Studies have found that the potential gains in China are even bigger, perhaps because of its cities’ surprising lack of density. Take Guangzhou, one of China’s more crowded cities. If it had the same density as Seoul, it could house an additional 4.2m people on its existing land, according to the World Bank.

But China’s government has long resisted the emergence of true megacities. It aims to prevent the population of its two biggest cities, Beijing and Shanghai, from exceeding 23m and 25m, respectively, in 2035—little bigger than they are today. City clusters are a workaround. In the jargon of urban planners, they represent “borrowed size”: cities can, in principle, have the benefits of agglomeration with fewer of the downsides such as congestion. Alain Bertaud of New York University says that, if integrated well, China’s city clusters could, thanks to their size, achieve levels of productivity never seen in other countries. He says it would be comparable to the differences between England and the rest of the world during the Industrial Revolution.

This vision of hyper-productive Chinese clusters is a pipe dream for now. The government first mentioned city clusters as a development strategy in 2006. It was not until 2016 that it elaborated the concept. Of its 19 identified clusters, just a few have published detailed plans so far. The gap between talk and policy remains vast. Officials have called for more region-wide governance, a welcome change from the municipal turf battles that have bedevilled China. In January the Yangtze River Delta area established an office for regional co-ordination, the first of its kind. But it is a bureaucratic minnow, with little more than a dozen employees. Stefan Rau of the Asian Development Bank says it is essential that regional offices have power over budgets if they are to play a useful role.

Lustrous clusters

Evidence about economic gains from clustering in China is promising, if limited. Counties enjoy a 6% boost in productivity from being tied into the Yangtze super-region, according to an article published last year in the Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy. But the researchers found few such gains in other regions. That might be because they looked at old data. A more recent study, published in April by the National Bureau of Economic Research in America, supported the idea of big knowledge spillovers in super-regions. When cities were connected by high-speed rail, the quantity and quality of academic papers by local researchers increased by nearly a third, according to the authors.

Sceptics, however, note that the most successful clusters tend not to be creations of the government. As China’s economy has modernised, the tendency towards concentration has been irresistible, especially in coastal areas. Some towns have specialised in electronics, others in the clothing industry and so on. There has also been much more migration to the coast than to other regions. It is the clusters that have coalesced naturally, especially the deltas of the Pearl and Yangtze rivers, that have the brightest prospects.

Beyond these coastal conurbations, the outlook is dimmer. Several of the 19 designated clusters seem fanciful. An economic zone linking Nanning, a poor provincial capital, to Haikou, a port on Hainan island, some 500km and a ferry crossing away, is unlikely to amount to much. The proposed cluster in the middle reaches of the Yangtze, a territory larger than Poland, is too expansive to make sense. Even within promising areas, government plans can be counter-productive. Beijing could benefit from shifting some of its universities and businesses to other cities in the Jingjinji region. But Xi Jinping, the president, has decided that an entirely new city, Xiong’an, should be created, some 100km away. A similar development closer to Beijing would have a better shot at success.

The main concern for those trying to lead productive lives across the vast super-regions is more mundane: how easy it is to get from A to B. The government classifies clusters as “one-hour economic zones” or “two-hour economic zones”, depending on the time it takes to cross the cluster by high-speed rail. But it often takes longer to get to train stations within cities than to travel by train between cities. Ding Shu works in Shanghai and lives in Kunshan, a satellite town linked to Shanghai by a subway. Factoring in her bus ride to the subway, security checks to enter the station, walking time and waiting time, she spends about four hours a day commuting. She says she is thinking about looking for a job closer to home. New rail lines to Shanghai might eventually help. But for now, Ms Ding sees herself as a victim of urban sprawl, not the denizen of a seamless city cluster.

0 Comments